In an exclusive interview, True Travel founder Henry Morley spoke to Huw Cordey, producer and director, about his life as a natural history documentarian, and the influence that comes with showcasing an ever-changing world.

Located in the remote reaches of the Indian Ocean, closer to the shores of Madagascar and Comoros than its capital of Victoria on Mahé Island in the Seychelles, Aldabra Atoll sits as one of the most isolated atoll’s in the world. The island has no permanent inhabitants, save for one small research base. Its inaccessibility also means it has escaped most of our modern world issues, retaining a rich biodiversity that makes it a refuge for many species; including some 152,000 giant tortoises – the world’s largest population of this reptile.

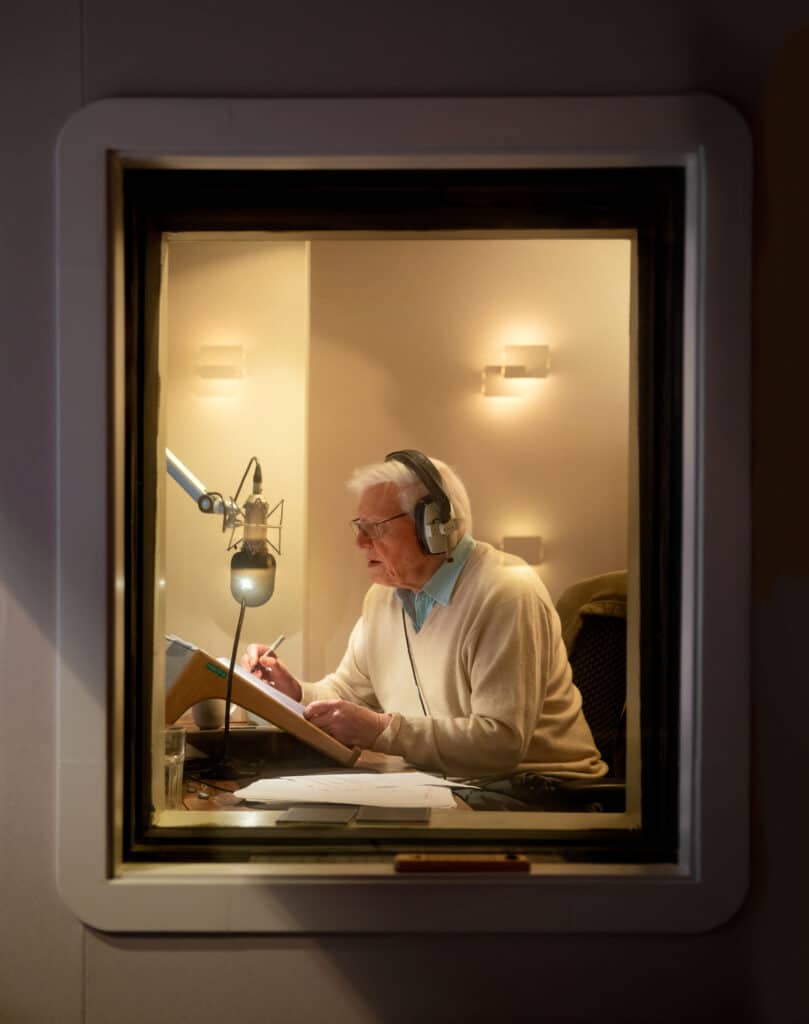

Huw Cordey, a name often credited next to the likes of Sir David Attenborough and Alastair Fothergill, is one of the few visitors. He set up a base to spend four weeks on the island, filming for A Perfect Planet, an esteemed natural history programme commissioned by the BBC and narrated by Attenborough himself.

With a 50 mile exclusion zone around it, nobody is allowed to even visit Aldabra; yet, Huw succeeded in navigating the red tape and was granted special permission to film there with his team. Arriving on the island, and ready to embark on a month of filming, the team were then faced with another, more shocking, challenge. Aldabra is one of the most remote atolls in the world, yet on one stretch of coastline in particular, it was hard to distinguish land beneath the sea of plastic.

“Humanity’s reach around the world is vast, and that’s one of the best examples to show that there’s really nowhere on the planet that doesn’t have our fingerprint on it.”

As the crew set about clearing the plastic waste, Huw lined up some of the thousands of washed up flip-flops to capture ‘Flip-flop Road’, “it was an ironic take on art and conservation”, Huw tells True Travel Founder, Henry, when recounting the story.

Huw Cordey has been behind the lens of some of the most revered natural history documentaries for over 30 years. His work spans from Planet Earth, to both instalments of Our Planet, and most recently he has been working with Netflix to film critically endangered orangutans in northern Sumatra. Cordey has worked on many of the series and films that have shifted the public perception of our environment monumentally over the last three decades.

One of the challenges Huw, and all natural history documentarians, face in their career is the pressure of improving your own work. “That’s what an audience wants. They want something bigger and better each time. That’s one of the great challenges of our industry. You can’t rest on your laurels because the animals are doing the same thing. You’ve got to present it and deliver it in a different way and make it fresh each time.” Over the years of Huw’s career to date, the continual development of technology seems to be leading the way in tackling this challenge. Having been part of the first natural history programme to use the Cineflex [a gyro stabilised camera system], to more recently filming with drones in Sumatra, he says: “The drones now are so good and so quiet, so small that you can do things that you just couldn’t have contemplated before. Even three years ago drones were too big and battery life too short.” So what is next? “I don’t know, VR or hologram television. I’m sure that’s just around the corner” he says with a wry smile.

So where did this all start for Huw? As a child he always had a fascination with the natural world, and a fervour for story-telling, but his pursuit of the arts instead of the sciences in education left him with no obvious way into what was then a very close-knit industry. However, after university Huw and a small group of friends were appointed the Mick Burke Award by the BBC to film their expedition cycling across the Himalayas. They were one of just four teams selected from ninety applicants – a testament to the potential he harboured even in the early days.

Perhaps a foreshadowing of his career to come, these formative years left an indelible mark on Cordey, but it didn’t make his success a guarantee. Natural history programming, especially within the epicentre of its production, is a magnificently competitive industry. Huw is humble in his accomplishments, telling Henry “even with the right background and motivation, you still need a bit of luck. And it’s then a question of making the most of that luck”.

In the early 90s, such luck came to fruition when Huw landed his first role in the industry with Partridge Films. As a specialist wildlife filmmaking company, and one of the very few outside of the BBC making quality content, Huw found himself working his way from the bottom up. It wouldn’t be until 1995 that he joined the team at the BBC Natural History Unit, which would act as his launchpad into working alongside the great Sir David Attenborough on the Life of Mammals.

Huw laughs as he recalls for Henry his first encounter with Attenborough, and how he inadvertently pushed the critically acclaimed naturalist to his limits by making him film with rats. Unbeknownst to Huw, as he smeared mashed banana onto stool legs in order to bring the rats closer to Attenborough’s feet, rats are the only animal of which he has a genuine phobia and dislike. A forgivable offence for an epic shot, though it’s perhaps unsurprising to learn that Attenborough hasn’t filmed in such close proximity to rats since.

In the years immediately following, Huw became well acquainted with Attenborough, working closely with him throughout the production process to bring some of the world’s greatest wildlife documentaries to life. Even now, just three years shy of a century, Attenborough has ‘retired’ to narration only, but is still blazing a trail for environmental conservation. On Huw’s latest project, a feature length film for Netflix, Attenborough’s voice carries viewers into the depths of Sumatra, tracing the footsteps of the critically endangered primate, the orangutan. There is collaboration, and negotiation, between the pair; as Huw tells it, “he’s got great judgement, but in addition to giving you good feedback on scripts, he makes changes that are better, as well as changes in just the way he likes to say things. He won’t just say something because it’s written”.

This is the artistry, and the craftsmanship, that brings the world to life. For people at home, Attenborough’s skills bring a slice of escapism so many need. For 60 minutes, viewers have the opportunity to become enthralled by a world beyond their doorstep. Each film is a masterpiece, crafted with tremendous care and attention and Henry nods in deep agreement as Huw summarises it so simply, “these are beautiful films, about beautiful places”.

In reality, there is a looming threat to this beauty. For a long while, production teams behind the scenes of these nature films omitted the existence of humanity. In the interest of preserving escapism for their audience, Huw admits that the presence of humans was a distraction. “We wanted to preserve the fiction that everything was fine. But, as time went on, it became clear that all was not well, and it could not be avoided.”

As his Silverback Films team prepared for the production of Netflix’s Our Planet (series 1), they felt it necessary to depict a more realistic version of the wilderness, one which could provide perspective for the viewer, and give an understanding of the problems faced in the natural world with an ever changing and polluted environment. It is a fine balance to achieve though, as ultimately, these documentaries are entertainment programmes, and with too much preaching, you lose your audience. Henry sympathises and explains to Huw that this is a sentiment we feel strongly within the travel industry also. We have a certain responsibility to tell and share the truth, but not to negate the excitement our clients – or in Huw’s case, audience – feel about the natural world.

Huw recognises this necessary equilibrium, telling Henry, “the education is a byproduct of the entertainment. Not the other way around. It’s not a lecture. It’s an entertaining story by which people can learn.”

Sharing these stories of the natural world is what is at the heart of Huw’s career. Duty cannot be misplaced, and despite his influential reach, Cordey, and the teams behind such productions, should not be looked to for solutions. Instead, their role within the larger fight against the climate crisis is founded on awareness and shifting the attitude of the public. Bringing emotion into their homes, and connecting them to a world they may not recognise, is simply the starting line for larger change.

With momentum, and a groundswell of public opinion, larger authorities and government bodies will begin to listen but as Huw so rightly remarks, “individuals can only do so much”. Henry echoes this sentiment, and throughout every facet of True Travel, has led from the front to engage a wider community in the efforts of positive impact travel. It is a collaboration, and the responsibility for real, tangible change does not lie in one place, but instead is made up of conversations like these. Where likened minds can indulge in their passions, voice their concerns and share their visions for the future.

Huw and Henry have found common ground in their fascination with the natural world and their passion to open the door for others to experience it. It is not a simple task, and is weighted with responsibility, yet with optimistic minds, tangible action and vivid story-telling, accessing the wild becomes a little less daunting.

Although the future of the natural world is undefined, Huw assures us of one thing, “we’re not going to run out of stories”.